|

|

+ Home | ||

|

||||

| + Solar Cycle Prediction | + Magnetograph | + The Sun in Time | + The Hinode Mission | + The STEREO Mission |

The Solar Interior

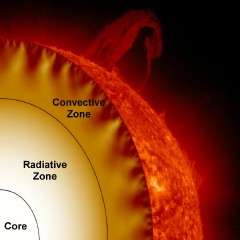

| The solar interior is separated into four regions by the different processes that occur there. Energy is generated in the core, the innermost 25%. This energy diffuses outward by radiation (mostly gamma-rays and x-rays) through the radiative zone and by convective fluid flows (boiling motion) through the convection zone, the outermost 30%. The thin interface layer (the "tachocline") between the radiative zone and the convection zone is where the Sun's magnetic field is thought to be generated. This animation, created by Leigh H. Kolb, audio-visual engineer, NASA’s/Marshall Space Flight Center depicts all the regions. | ||

The Core

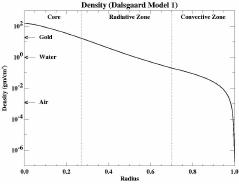

The Sun's core is the central region where nuclear reactions consume

hydrogen to form helium. These reactions release the energy that ultimately leaves the

surface as visible light. These reactions are highly sensitive to temperature and density.

The individual hydrogen nuclei must collide with enough energy to give a reasonable

probability of overcoming the repulsive electrical force between these two positively

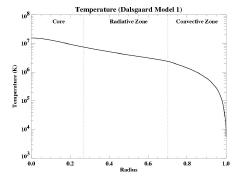

charged particles. The temperature at the very center of the Sun is about 15,000,000° C

(27,000,000° F) and the density is about 150 g/cm³ (approximately 10 times the density of gold, 19.3 g/cm³ or lead, 11.3 g/cm³). Both the temperature and the density decrease as one moves outward from the

center of the Sun. The nuclear burning is almost completely shut off beyond the outer edge

of the core (about 25% of the distance to the surface or 175,000 km from the center). At

that point the temperature is only half its central value and the density drops to about

20 g/cm³.

| |||

|

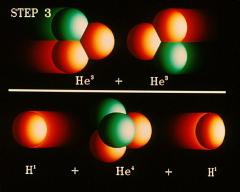

In stars like the Sun the nuclear burning takes place through a three step process called the proton-proton or pp chain. In the first step two protons collide to produce deuterium, a positron, and a neutrino. In the second step a proton collides with the deuterium to produce a helium-3 nucleus and a gamma ray. In the third step two helium-3s collide to produce a normal helium-4 nucleus with the release of two protons. | ||

|

In this process of fusing hydrogen to form helium, the nuclear reactions

produce elementary particles called neutrinos. These elusive particles pass right

through the overlying layers of the Sun and, with some effort, can be detected here on

Earth. The number of neutrinos we detect is but a fraction of the number we expected. This

problem of the missing neutrinos was one of the great

mysteries of solar astronomy but now appears to be solved by the discovery

of neutrino masses. | |||

The Radiative Zone | |||

|

The radiative zone extends outward from the outer edge of the core to the interface layer or tachocline at the base of the convection zone (from 25% of the distance to the surface to 70% of that distance). The radiative zone is characterized by the method of energy transport - radiation. The energy generated in the core is carried by light (photons) that bounces from particle to particle through the radiative zone. | ||

|

Although the photons travel at the speed of light, they bounce so many times through this dense

material that an individual photon takes about a million years to finally reach the

interface layer. The density drops from 20 g/cm³ (about the density of gold) down to only

0.2 g/cm³ (less than the density of water) from the bottom to the top of the radiative

zone. The temperature falls from 7,000,000° C to about 2,000,000° C over the same

distance. | |||

The Interface Layer (Tachocline) | |||

|

The interface layer lies between the radiative zone and the convective zone. The fluid motions found in the convection zone slowly disappear from the top of this layer to its bottom where the conditions match those of the calm radiative zone. This thin layer has become more interesting in recent years as more details have been discovered about it. | ||

|

It is now believed that the Sun's magnetic field is generated by a magnetic dynamo in this layer. The changes in fluid flow velocities

across the layer (shear flows) can stretch magnetic field lines of force and make

them stronger. This change in flow velocity gives this layer its alternative

name - the tachocline. There also appears to be sudden changes in chemical composition across this

layer. | |||

The Convection Zone | |||

|

The convection zone is the outer-most layer of the solar interior. It extends from a depth of about 200,000 km right up to the visible surface. At the base of the convection zone the temperature is about 2,000,000° C. This is "cool" enough for the heavier ions (such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, calcium, and iron) to hold onto some of their electrons. This makes the material more opaque so that it is harder for radiation to get through. This traps heat that ultimately makes the fluid unstable and it starts to "boil" or convect. | ||

|

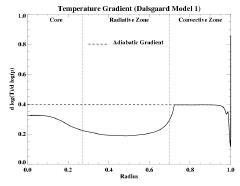

Convection occurs when the temperature gradient (the rate at which the temperature falls with height or radius) gets larger than the adiabatic gradient (the rate at which the temperature would fall if a volume of material were moved higher without adding heat). Where this occurs a volume of material moved upward will be warmer than its surroundings and will continue to rise further. These convective motions carry heat quite rapidly to the surface. The fluid expands and cools as it rises. At the visible surface the temperature has dropped to 5,700 K and the density is only 0.0000002 gm/cm³ (about 1/10,000th the density of air at sea level). The convective motions themselves are visible at the surface as granules and supergranules. | |||